Inside the Kurt Cobain Business

Two days after Kurt Cobain’s body was found in the greenhouse of their Seattle home, Courtney Love showed up late to a raucous candlelit gathering of distraught Nirvana fans. She played a grief-stricken, vulgar recording of herself reading part of his suicide note, led the crowd in a chant calling Cobain an “asshole,” and handed out some of Cobain’s clothes, which she continued to do in the weeks that followed. Twenty-five years later, one of the sweaters that Love gave to a family friend is expected to fetch $300,000 at an auction this weekend.

“Courtney couldn’t have realized that the value of these things would be worth what they are today,” Darren Julien, who is running that auction, tells Fortune. “Those are John Lennon prices.”

The most reticent of rock stars—one who agonized about his artistic truth being fed into the thresher of corporatism—now commands his own economy from beyond the grave. In 1991, the cover of Nirvana’s major-label debut, Nevermind, satirically depicted a baby chasing a dollar bill on a fishhook. In 2019, the Kurt Cobain business is big business.

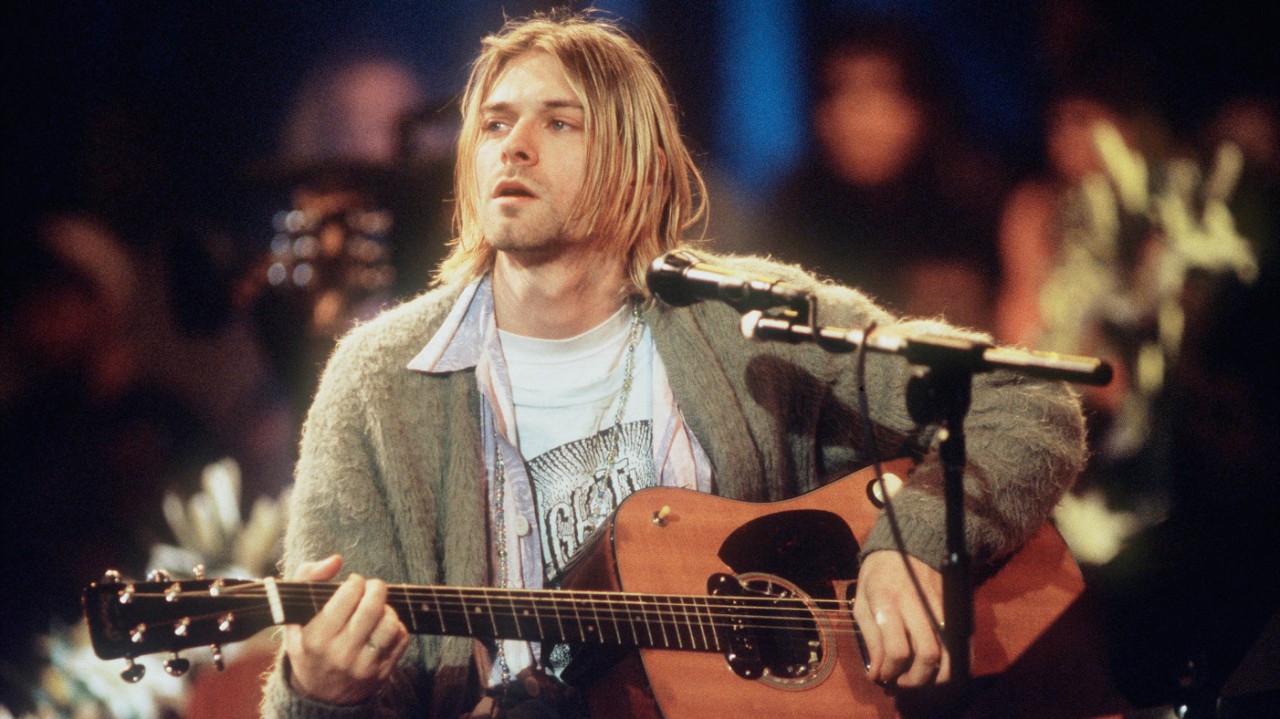

Julien, the founder, president, and chief executive officer of Julien’s Auctions presides over many offbeat Cobain sales, including a sodden pizza plate-turned setlist that sold for $22,400 after being estimated at only $1,000 or $2,000. This Friday and Saturday, Cobain’s MTV Unplugged cardigan and one of his custom-built Fender Mustangs will hit the auction block once again for Julien Live’s Icons and Idols auction; taken together, the items could command over half a million dollars. (As of Tuesday, the cardigan had already drawn a bid of $200,000.)

Cobain was named the highest-paid dead celebrity of 2006 by Forbes and is still in the most profitable echelon of late rock stars. This includes music and design licensing, stray clothes, and instruments, and film and book deals. Not to mention Nirvana’s publishing rights, a large portion of which was purchased from Love’s estate by Primary Wave’s Larry Mestel in 2006 for an estimated $50 million before the company divested its interest as part of a $150 million deal with BMG. In 2014, Cobain’s estate was estimated at $450 million.

Like Marilyn Monroe’s, Jimi Hendrix’s, and Tupac Shakur’s, Cobain’s life and career spanned the course of a few explosive years, leaving a small amount of wildly collectible items in the world. While he filled notebooks with writing and made countless pieces of quirky visual art, most of it remains privately owned. With precious few Cobain items out there, collectors tend to rely on acts of flukish generosity—like Love passing out his clothing at the 1994 vigil.

“His career and life was so short that there isn’t a lot of Kurt-owned material or guitars out there. They just don’t exist,” says Bobby Livingston, the executive vice president of public relations at RR Auction. “It’s going to become harder and harder to find those types of items, especially that are iconic to his career.”

In March 2019, RR Auction put the hospital gown worn by Cobain at England’s Reading Festival in 1992 on the auction block. The gown carries a hell of a story: on Aug. 18, 1992, Cobain was withdrawing from heroin at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Love was in a nearby room due to give birth to Frances Bean Cobain. Unwilling to deliver without Cobain nearby, she picked up her IV, stormed into his room and dragged him into hers.

Two weeks later, at one of the biggest concerts of Nirvana’s career, Cobain was playfully wheeled onstage in a wheelchair before tearing into a ferocious set—with his Cedars-Sinai gown over his clothes. Covered in mysterious stains possibly related to his drug addiction and/or his child’s birth, it was one of the items passed out by Love at his vigil.

Despite its clout among Nirvana fans, the gown stalled out at around $23,000 on the auction block—nowhere near what the MTV Unplugged sweater commands in 2019. Livingston is disappointed by this, calling the gown unappreciated.

“It was withdrawn by the consigner because he was expecting more,” he says. “That MTV concert, that particular sweater, that was shown over and over and over and over and over and over again [after his death]. It might have just resonated more in the marketplace.”

Again, he chalks it up to the paucity of items that Love handed out to fans and friends. “I think Courtney was extremely upset, obviously devastated by what had happened and touched by these fans, and she just brought a handful of stuff out that day,” he says. “It’s not like she brought a truck with her.”

“Kurt’s a great example of not having a lot of items out there right now,” says David Frangioni, a collector and recording engineer who appraises and collects historically valuable instruments. “When you look at the item rather than the artist, that’s when you really determine, well, what’s the scarcity of that? And in most cases, there’s one of one.”

Garry Shrum, public relations specialist at Heritage Auctions, currently has a host of Nirvana handbills, ticket artwork, and concert posters up for auction, including a very early flier for a 1988 gig at Squid Row Tavern in Seattle—three years before the Nirvana boom.

“Nothing was taken real serious. Nobody thought that anybody would keep these posters and want these posters in the future,” Shrum says. “They were so low budget that people just threw them away.”

It’s not just physical collectibles touched by Cobain making big money. In 2002, Riverhead Books released Kurt Cobain: Journals, a collection of his scrawlings in stray notebooks: band business, tormented song ideas, even shopping lists.

Early on in Journals, a page reads: “Please read my diary, look through my things and figure me out.” Still, Cobain, who had been dead for almost a decade, couldn’t have signed off on his private writings becoming available to the entire planet. As Cobain biographer Charles R. Cross told Entertainment Weekly in 2002, “stuff was being ripped off from Kurt’s house left and right” after his passing.

While visiting his home, Cobain’s friend, Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson, serendipitously scooped up his stray papers and spiral-bound notebooks. “There were a lot of people hanging around there whose drug problems were significant, and Erlandson had the foresight to gather up Kurt’s belongings and put them away,” Cross said.

While Cross wrote 2001’s Heavier Than Heaven: A Biography of Kurt Cobain, Love supplied him with some of Cobain’s notebooks. Eventually, the writings were turned over to Jim Barber, Love’s manager-turned-boyfriend, and selections from 23 of his notebooks resulted in a multi-million-dollar deal with Riverhead Books, a subsidiary of Penguin Putnam.

"He's not here and [the estate's] responsibility is to promote his creativity and his legacy," Barber told the Seattle Times in 2002. “[There’s] some really cool stuff.”

“The most violating thing I've felt this year is not the media exaggerations or the catchy gossip, but the rape of my personal thoughts,” Cobain writes on one page. Upon its release in 2002, Journals became a New York Times nonfiction bestseller, and it’s still available at Urban Outfitters, Barnes & Noble, and anywhere else books are sold.

The Cobain business bleeds into fashion, too. In 2018, Nirvana’s x-eyed smiley face logo, originally designed by Cobain, was included by Marc Jacobs in his Bootleg Redux Grunge collection, a revival of Jacobs’s 1993 Perry Ellis collection that gave 1990s style a blast of flanneled attitude.

The new collection took the theme slightly too far by rolling out a shirt with a slightly modified Nirvana smiley design with “Heaven” instead of the band’s name. Marc Jacobs was slapped with a lawsuit by Nirvana L.L.C., an entity helmed by surviving Nirvana members Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl; the fashion giant contested the suit with a publicly released logo comparison table.

“The word NIRVANA [is] not used,” the table reads. “[It uses] a smiley face with (a) an M and a J as eyes, (b) a squiggly line for a mouth with a tongue protruding therefrom and (c) a roughly circular facial outline.” At press time, both sides are preparing for trial.

“The matter could potentially settle... for an amount less than what Marc Jacobs would have to pay to secure Nirvana's consent from the get-go,” Elizabeth Kurpis, a New York fashion lawyer, told Vogue Business in 2019. “I can only assume they knew the risks of using an image that so closely resembles the iconic Nirvana image, and accordingly came prepared for the fight.”

Whether in the courtroom or on the auction block, the Cobain business is only growing legs. “Nirvana is the last great band,” Livingston says.

“I see the prices escalating for a while,” Shrum predicts.

Julien even sees the future of the Cobain business as going beyond rock ‘n roll collecting and into portfolio diversification. “Pop culture has become the new fine art. Not everyone’s going to be interested in Monets forever,” he says.

In the 1992 liner notes for Nirvana’s Incesticide, Cobain railed against “music industry plankton,” dismissed the “million dollars [he] made last year” and decreed that punk rock was “dead and gone.”

“A big ‘fuck you’ to those of you who have the audacity to claim that I'm so naive and stupid that I would allow myself to be taken advantage of and manipulated,” he wrote. “I don't feel the least bit guilty for commercially exploiting a completely exhausted rock youth culture.”

In 2019, Cobain is irreversibly part of the commercial landscape—whether he signed off on it or not. With Julien’s Icons and Idols auction, the miniature economy of anything he touched, wore, or played seems to just be getting started. As Cobain sarcastically snarled onstage in 1992 while covering an obscure hardcore punk song by Fang, the money will roll right in.